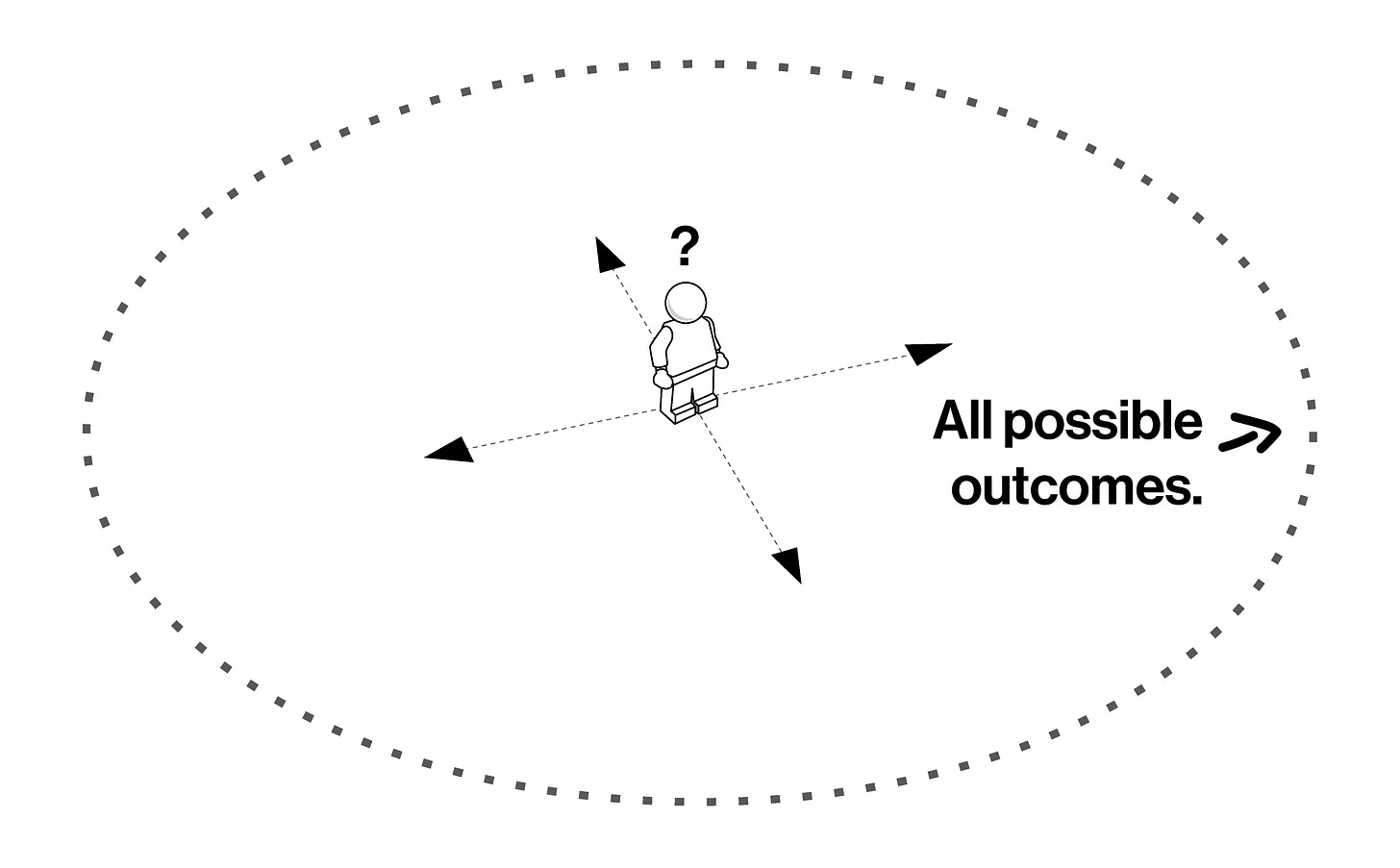

You are standing in the middle of a vast plain.

In every direction, the horizon blends seamlessly into the sky. Surrounding you, just beyond your ability to see, lie all the possible endpoints for your upcoming journey–an infinite number of them.

You’re trying to reach the right one, but you don’t know which one it is—or even which direction will lead you there. Every design project begins in this place of ambiguity—whether you’re creating a logo, a building, a product, a service, or an entire business. How do you start when you don’t know where you’re trying to go?

You could take a very, very long walk

One way to approach decision-making is to understand every possible outcome in detail, aiming for a complete picture before choosing a direction.

Imagine moving out closer to the edge of the plain. Now, you can see a mountain straight ahead with a forest on one side and a lake to the other. You begin to walk slowly around the edge, surveying all the features as they come into view. In another direction you find a desert, and even further along an icy river which cuts through a snowfield. Slowly you develop a detailed understanding of what lies in each direction. In an ideal world, this long journey would give you all the information needed to make the best decision.

In reality, this approach is time-consuming and expensive–it takes massive resources to visualize all possible outcomes in detail. You will run out of time, money, or enthusiasm before making meaningful progress, and you risk being paralyzed by analysis. This approach tries to eliminate ambiguity, but perfect information for decision-making is impractical. You need a way to cut through ambiguity instead.

I’ve seen large, hierarchical, risk averse organizations get stuck taking this approach. This common failure mode occurs when no one has clear authority to take a chance.

Example: A library of digital photography ideas

At IDEO, I worked with a team to help a major corporation redesign their digital photography offering. In the beginning, excitement ran high over the potential to create a breakthrough experience for customers. For months, we explored every aspect of digital photography—capturing and sharing images, creating books, and more. Although we generated a vast idea library for envisioning the future, we struggled with choosing a clear direction. The project ended with our enthusiasm drained and no decisive action.

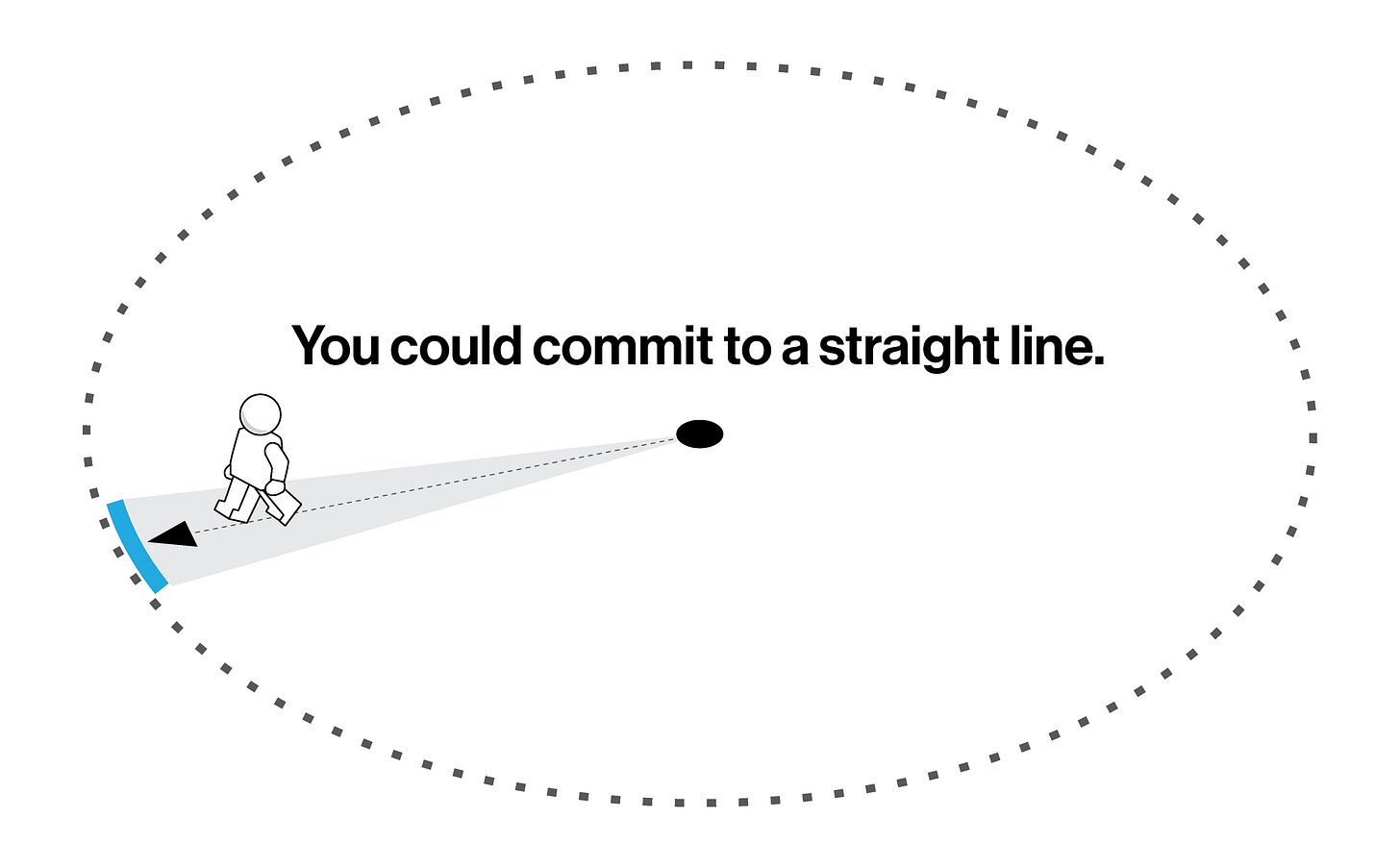

You could commit to a straight line

Another approach is to pick a direction and go for it.

Traveling light, you move fast and break things. The feeling of progress and momentum is intoxicating. In the distance, you see your goal—a mountain looming on the horizon. As you move forward, you encounter obstacles: a creek to cross, boulders to scramble over. The grade ticks upwards, and progress slows. False summits reveal just how far you still have to go. Trails branch off in other directions, but you ignore them. By now, you’ve come so far that there’s little time or appetite for questions. Any uncertainty is pushed aside as you are compelled by the allure of the mountain—until the path is impassable. Progress grinds to a halt before reaching the final destination.

I’ve seen this scenario play out at small, vision-led startups. The team sets off on a predetermined straight line. With limited resources and tunnel vision, execution is the focus from day one. Conservatively, about 75% of startups fail. When there is only one narrow chance to get it right, many end up in the very large pile of failed ideas.

Example: Focused on email

I co-founded a startup called Tylr Mobile, we envisioned a suite of apps to increase the productivity of mobile workforces. Our first idea was an email app for salespeople, and we pursued it with singular focus. We soon learned that building a great email app is technically challenging, and our progress was slow. As the designer, I visualized alternate paths for our first product, hoping to shift toward an easier initial target. But we were married to the email problem and stuck with it until we were almost out of money. At the last minute, we tried to pivot, but it was too late. With our first product still in beta, Tylr joined the legion of failed Silicon Valley startups.

You could look around, walk a bit, and look around again

As a professor of design, I teach balanced exploration.

From the center, move farther out into the vast plain—but not all the way to the edge. Take a shorter walk around and scan the landscape. Should you head toward the mountains? The lakes region? The open plains? Now, with a broader view, you have some information to help narrow down your options. Moving outward again along your chosen, narrower path, more details come into focus. Obstacles and opportunities emerge into view ahead.

As you focus on a smaller set of possibilities, you can dive deeper, gaining a more detailed understanding of the potential trade-offs of each path. With each cycle of this iterative process, you build greater confidence in your direction and move closer to your desired outcome.

Example: Balanced exploration for the Rootstock logo

Rootstock is a startup accelerating the transition to regenerative agriculture. Soil health, quality produce, and collaboration are core to its mission. What should Rootstock’s logo be?

I started with quick sketches to share with the founder. We looked at multiple ways to capture the unique character of Rootstock. Did we want to focus on the collaborative, community oriented aspects of Rootstock? Focus on the end goal of quality produce at the marketplace? Or on soil health?

As we explored design refinements, we were drawn to elements that told stories of above and below ground—reminders of the roots and soil that sustain everything we see on the surface.

We thought the overlapping Os and the OC could visually capture the connections central to the initiative: our connection to growing communities, to the food we grow, and to the land it grows on.

With the final elements in focus, we then explored balance and emphasis of the elements.

The final Rootstock logo.

Intentional design decision making

Balanced exploration reminds me to pause periodically, look around, and ensure I’m still heading in the right direction. I strive to be intentional with each decision in a design project while recognizing and understanding compromises along the way. Choosing one path rules out all others—even if you haven’t considered all the other paths. If you don’t see compromises in your design decisions, you’re not paying close enough attention.

No matter what you’re designing—whether a logo, building, product, service, or business—navigating ambiguity is essential. Creating something from nothing has always been challenging. But with technology that makes it possible to bring any idea to life, honing our ability to discern what we should make is more important than ever.

I hope this model helps you navigate uncertainty and find the best possible outcome—whatever it is you’re designing.

I recently learned a supportive crew helps overcome the resistance.

Julia Sunderland - Founder of Rootstock. Thanks for the logo project and the edits!

Sawani Mardhekar - Student at the CCA. Thanks for the feedback.

– For incredible attention to detail. You made me sound like a much more efficient version of myself.Leo Kopelow – Long time friend and colleague who still puts up with me and helps me clarify my thoughts.

For helping me find my shiny dime and cut my darlings:

, Samantha Law, , , ,

Balanced exploration makes sense—but it reminds me of the time I tried to navigate ambiguity in a completely different way… involving a mango, a compass, and a very confused goat. Still working through what I learned from that.

Great piece, Matthew. I loved showing us the spectrum of choices in how we navigate ambiguity, and show us the virtue in balanced exploration. Very interesting.