As the group settled into their seats, I caught the first sign of trouble—the body language. Slouched postures, crossed arms, grumpy expressions. It was my first week at my new gig, and I was attempting to run a brainstorm. My new engineering colleagues looked skeptical and annoyed, like they wanted to be anywhere but here. This was an important first step in the project, but things weren’t off to a great start.

It was January 2008 and I had just joined Palm, a struggling Silicon Valley device manufacturer. Before that, I spent seven years at IDEO, my dream job, where brainstorming and collaboration are core to the culture. Widely considered the world’s leading design consulting firm, IDEO is known for iconic innovations like the original Apple Mouse, stand-up no-mess toothpaste tubes, and the redesign of the common shopping cart—famously captured in an ABC News Nightline special.

At IDEO, I collaborated on an insane diversity of projects—healthcare systems with Kaiser Permanente, a mobile music streaming service for AT&T, exercise equipment with Precor, and future visions of XBOX for Microsoft, among others. I got comfortable entering brand new domains with a beginner's mind, each offering an incredible learning opportunity. It was an extremely collaborative environment full of positive, optimistic people. I looked forward to being hunkered down in the project space with a team—confident that a thrilling insight about our project would soon come into view. In the years since, many people have asked me, “why did you ever leave?”

We came up with a lot of great ideas for products, services and environments. As much as I enjoyed that work, I rarely had the experience of seeing a project all the way through to an actual product launch—so many of our ideas were confined to slide presentations and fancy spiral bound books at the end of an engagement. The few projects I worked on that did make it to market hardly resembled our original vision.

For one project, we designed a package for on-the-go salad eating. It highlighted the cheese, nuts, and other exciting parts of the salad—what we called the “jewels.’ The cap that held them flipped over and snapped back on, expanding the container’s volume. This would let the eater shake the container to toss salad easily without the dressing being stuck to the lid. We also designed the ideal salad utensil that works like tongs, a fork, and chopsticks all-in-one.

Months later while shopping, I spotted something that looked kind of like what I worked on… a little bit. The cool utensil was there. The jewels were on display. But it didn’t do the expanding volume trick. Today you can still find the distant cousin of our idea on the company’s website. Now it comes with a standard plastic fork.

I started thinking about leaving IDEO, a wanderlust fueled by a desire to ship products rather than just making compelling presentations about what other people should make.

When a recruiter called about a job at Palm, I nearly hung up. Who would leave this designer’s utopia for a company long past its heyday? Once famous for the Palm Pilot personal digital assistant, the company hadn’t done much of note in years. No, thanks.

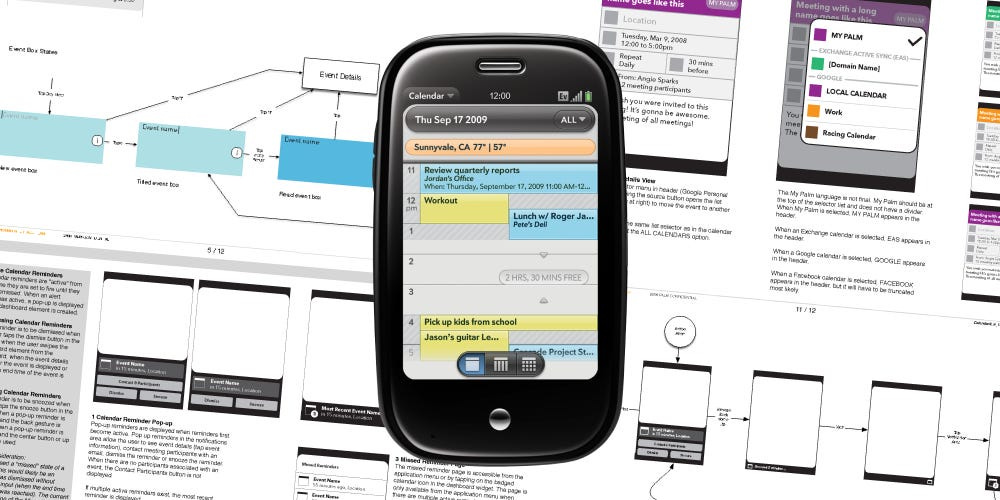

But I stayed on the line with the recruiter. Palm was attempting to reclaim its former glory with a new mobile phone and multi-touch operating system. It was a rare chance to design a mobile OS from the ground up. I realized I’d either gain the experience of shipping a product or watch the company fail while trying. Either way, a valuable learning experience. After seven years of training in the IDEO approach, I left design consulting and leapt into the ring.

Let’s get ready to RUMBLE

And that’s how I found myself leading a brainstorm in unfamiliar territory—my new Palm colleagues slouched around the conference table, arms crossed, grumpy expressions.

I had organized the meeting to kick off the design phase of a new app. Palm’s conference rooms weren’t set up for brainstorms like the ones at IDEO, so on my way to work, I stopped at an office supply store for Post-it notes and Sharpies.

I brought Sharpies; I didn’t know it was a knife fight.

I kicked off the session with a series of brainstorm questions, hoping to spark ideas. I repeated my prepared questions, holding out my pad of Post-its like a catcher’s mitt—ready to grab any idea they might offer.

If only they would say something. Anything.

I tried to lead by example, scribbling my own thoughts onto Post-its and sticking them to the wall. Now they leaned in. Ideas to tear down. Fresh meat.

“We tried that before!”

“You can’t do that! That will never work!”

“What about this problem? What about that problem?”

These engineers didn’t see early-stage idea generation as part of their role. They wanted to be told what to build rather than be involved in generating the ideas. They left the idea generation entirely to me, and proceeded to tear down the ideas I contributed.

At IDEO, we valued generating lots of ideas—from anyone, at every stage. The more ideas, the better the chances of finding a great one. We built on each other’s ideas with little concern for who came up with what.

My failed brainstorm was disorienting. I was exhausted. I had taken a few hits and retreated to my corner to shake it off. Undeterred. I still believed that collaboration would ultimately win.

When I participated in meetings run by others, I ran into a similar dynamic.

My experience in design had taught me to walk into a conference room assuming that I did not know the answer to the question at hand. I knew how to help a team find a great answer to a problem, and I learned to bring a beginners' mind to any discussion. I saw meetings as an opportunity to leverage multiple perspectives of a diverse team. I wanted to uncover opportunities that no individual would have seen on their own.

I found my Palm colleagues often took a different approach. They came in ready to fight for the idea they already had.

My colleagues entered the room, sizing each other up. Who was invited to this session? Who made time for it on their calendar? Who was willing to go toe-to-toe?

Some days it was seniority that won the day. Other times it was simply volume or persistence that prevailed. I missed the excitement of leaving the room knowing more than when we walked in—a real sense of discovery. On many occasions I rose in defense of an idea held by a less assertive member of the team—can we at least hear them out please?

Cut, bruised, and swollen—but I was making slow progress. I tried to get to know each engineer I worked with a little bit better and I adjusted my approach accordingly. Some still preferred to wait until every t was crossed and every i dotted before talking to me; but others became eager to collaborate. Some days, it felt less like surviving ten rounds and more like we were actually working with each other.

Progress—but at a cost. After a couple years, there were mornings I struggled to drag myself out of bed to go to work. I was still excited about what we were building, but the friction between how I wanted to work and the company’s norms wore me down. I considered joining the ranks of the IDEO boomerangers—people who ventured from our spiritual home and returned soon after their first bout with the outside world.

But I wasn’t ready to give up after round one. When a recruiter reached out about a venture-backed, stealth-mode startup hiring its tenth employee, it sounded exciting—so I signed up.

DING DING DING! Round two!

It was exciting to be employee #10 at a real life startup. Things moved fast—every day brought a new priority-one issue. Then we invented a higher tier called “en fuego” for problems that were somehow even more urgent. Everything was always on fire, and some days, I struggled to keep up. It all felt harder than it needed to be. I supposed this was the startup game.

When the company grew to 20 people, the founders started formal onboarding sessions—an intentional effort to shape company culture. The CTO laid out his vision, instructing us to see our colleagues as competitors. By constantly trying to outdo each other, he explained, we would drive high performance and ensure the company’s success.

I had a vision of my new colleagues cutting throats and clambering over fallen bodies to get to the top as I watched quietly from the corner. How did I end up in this place? I thought. Here we go again.

I worked closely with the CEO, who set the product vision. He often tasked me with refining the details of his big ideas. As I worked, new possibilities emerged—not with the purpose of challenging his vision, but as a natural result of exploration. I never returned with just one idea. I brought back his original concept plus alternatives, outlining their pros and cons. Sometimes, I thought I’d found a better way forward.

I didn’t see it coming when I walked face-first into a 1-2-3 combo of idea-hating.

“Hey boss, check this out…”

“I hate it. Just do it my way.”

Pop. A quick jab to the face.

“I looked at this again and made some adjustments.”

“I hate it even more.” A pause. “I understand what you’re saying. Do it my way anyway.”

Boom. Boom. Boom. A barrage of body shots… I blocked, parried, and stepped back. I kept my feet.

“OK, I think I’ve got your idea ready to go… but I still think this one is worth considering.”

“I hate it the most.” Another pause. “...But fine. We’ll do it your way.”

Persistence and endurance won a round now and then, but the battle was exhausting. Again, after about two years I threw in the towel and I moved on to my next adventure.

I had a rough landing after leaving IDEO, but each experience helped me refine what I was looking for in a workplace. I became more intentional about seeking out collaborative, low-ego cultures, often reconnecting with former colleagues who shared my perspective on how great teams should operate.

I teamed up with a colleague from Palm to build and lead a design team for an internet startup. Later, I joined another ex-Palm collaborator to create a smart fridge magnet—a device that scanned barcodes and used voice input to update grocery lists. I launched my independent consulting business by helping a former IDEO colleague with his wearable technology startup.

Each of these teams thrived on collaboration, fluid teamwork and shared ownership.

Creating the World I Want to See, One Project, One Class at a Time

Today, I bring a collaborative mindset to my design consulting projects and to my teaching at California College of the Arts, where I work with Master’s students in the Interaction Design program. I was fortunate to learn the value of collaboration in school and through my experience at IDEO. Now, I make a point to bring this perspective into the classroom because, for many of my students, it’s something they haven’t encountered before.

I give them reliable, repeatable frameworks for tackling complex, ambiguous design problems so they feel confident taking on big challenges and building things that matter. But the future won’t be shaped by lone geniuses. Our biggest, most wicked challenges will require the collective expertise of diverse, empowered teams.

I teach my students what I’ve learned about collaboration—and I give them opportunities to practice it. Since I know they won’t always land in supportive environments, I share my war stories and the strategies I’ve used to navigate difficult team dynamics.

Building meaningful products isn’t a five-minute wrestling match. We can’t fight our way to where we need to go. Instead, we need to focus our collective energy on the problems we’re trying to solve, assembling teams with diverse experience and bringing out their best.

It’s more like a marathon than a combat sport—one we all have to run together.

Wow, this was a hard essay to write. Lots of people helped me remember details, clarify my ideas, and finally (after many attempts) land the plane.

I had to jog my memory about old projects. It was fun reconnecting with old IDEO colleagues Bosung Kim, inventor of the Forkchops; Ted Barber, who worked on the salad package project after I had moved off the team; and Leo Kopelow whom I worked closely with throughout my time at IDEO.

In late 2024, I took an online writing course called Write Of Passage. It helped me get off my ass and finally start a writing habit. The course is no longer with us, but the community persists. Many thanks to my fellow writers for helping me out by reviewing one of the MANY drafts of this essay.

, , , , , Phil Chiu, , ,In addition to writing about design, I write about my tiny misadventures in music in in

. Check it out!

It’s always enjoyable to read your ‘posts’. They make me very proud. Well written and insightful; You’ll probably never know the number of students you’ve affected.

I still remember the first time an IT colleague (of whom I am quite fond) sat me down and said, “Melody, I hate ideation. Stop trying to get me to do this. Do the design and I’ll tell you what’s not working with it.” Like you, I was no longer in Designlandia.