What Problem Are You Trying to Solve?

Why Investigating the Problem Leads to the Best Solutions

“What problem are you trying to solve?”

Barely a minute into presenting my work, 25-year-old me is brusquely interrupted by my gruff, bearded professor, John Grimes.

Disoriented and annoyed that he spoke to me like I was 10 years old, I paused briefly, unsure how to respond. I continued as if nothing had happened, explaining my solution for an augmented reality display interface that provides the user step-by-step instructions. I walked the class through where I'd placed the controls and how they function when activated by clever eye-tracking technology. Next, I began to describe the colors I’d chosen—

“What problem are you trying to solve?”

The pattern repeated until my five minutes were up. Frustrated, I returned to my seat. This was my first interaction design class as a Master of Design student at the Institute of Design in Chicago.

My struggle continued until about halfway through the semester, when I finally began to understand the purpose of his interruptions. Grimes wanted us to start with the problem, not the solution, but I struggled to understand what that meant or why I would want to do that.

This approach and its value were reinforced in other classes, most notably in my systems design course, where I was introduced to Christopher Alexander’s Notes on the Synthesis of Form (Amazon). This book's central and fundamental lesson is that a detailed understanding of a problem is a necessary first step to discovering solutions. I found Alexander’s writing clear, insightful, and inspiring.

The Goodness of Fit

In Notes, Alexander suggests that designers should think not only about what we create—what he refers to as the "form"—but also the environment where the form exists (or its "context"). The context represents the problem, and the form is the solution; together, they create what Alexander calls the "ensemble."

The "goodness" of an ensemble is determined by how well the form fits the context.

When I embraced this approach, I realized that with a sufficient understanding of the context, the form almost reveals itself. It’s not about a high-level problem statement, but rather a detailed analysis of the many small problems that collectively comprise a big one. A close examination—breaking the big problem into smaller, more manageable pieces—uncovers new possibilities and unexpected potential forms.

The most exciting moments in my design career have felt like discoveries of something already there and hidden in plain sight. I’ve learned that understanding the details of a problem is the starting point for defining a new form that clicks into place. Now as a design teacher myself, I strive to pass this conviction on to my students.

How can I teach this?

“What problem are you trying to solve?”

I want my students to have the same epiphany I did—so I give them the same treatment I got. I ask them the same question and assign Alexander’s book.

Now I understand better why this lesson was hard for me to learn—it is profoundly counterintuitive to a young design student. Design students are excited to make things. They want to be anointed the title of designer and finally wield the hard-won authority to define forms—deciding what shape things should be, typefaces to use, what buttons things should have, and where they should go. As a student, I wanted to start with the form, and most of my students have the same idea.

I want my students to experience the thrill of discovering a design solution through a deep investigation of context. But truly understanding the context of a design challenge is difficult—if not impossible—from inside the classroom.

As designers, we have tried-and-true methods for both collecting data and prototyping potential solutions.

Bridging the gap between research and prototyping is the real challenge. Moving from research data to an actionable understanding of context is a crucial step, yet it isn’t as well understood or systematically taught as the practices of research and prototyping.

How can I inspire my students to focus on context within the constraints of a three-hour studio class?

Kitchen of the Future

Each semester, I lead my new crop of students in a three-hour project called “Kitchen of the Future.” In this project, a fictitious client—a household goods manufacturer—seeks opportunities to create new food storage solutions for busy families. The first step of this design exploration is to visit people’s kitchens and understand the context: What problems and opportunities do they face regarding food storage?

Because this kind of fieldwork is difficult to accomplish within the constraints of a classroom, I do it for them. To develop this lesson, I reached out to some of my brilliant colleagues and enlisted their help. We each visited the kitchens of busy families, capturing video of one-hour interviews to understand current food storage experiences and practices. I then edited these hours of footage into a 20 minute highlight reel, packed with observations and stories about how busy families store food. I use this video to teach them a reliable and repeatable way to make sense of raw design research data.

Translating Observations into Insights

During class, then, we watch the 20-minute video together while armed with stacks of Post-it notes and Sharpie markers to capture observations. The video serves as a proxy for real-world field experience, giving students a window into the context of our fictitious project. From there, I guide them through my process for translating raw data from the field into something actionable for design—a grounded, clear point of view of the context.

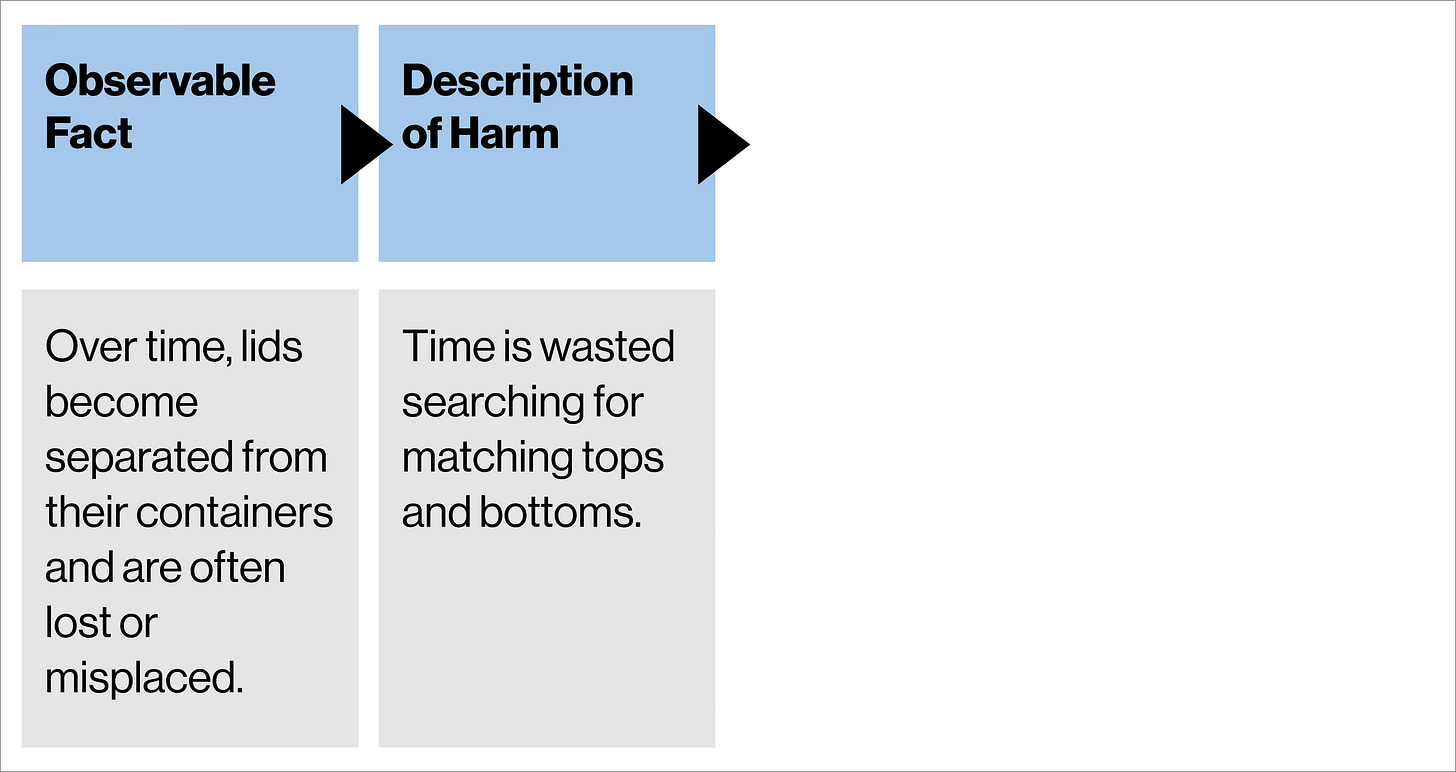

I ask students to jot down notes for anything they see or hear in the video that feels like a defining aspect of the context we’re designing for. I emphasize the importance of capturing observable facts that illustrate problems—things that don’t work. This is the starting point of a grounded definition of the context, which, in turn, will define the form.

Describe the Harm

The next step is to define the harm or opportunity evident in the observations. For each observation, I ask my students: "What’s wrong with what you see here?" I encourage them to frame the harm in terms of a compromised value such as time, wealth, wisdom, love, curiosity, or creativity.

While observations are objective facts about the world, this step—describing the harm—is a judgment, an opinion grounded in observation. Different designers may interpret an observation in different ways. Many observable facts in the video don't point to a compromised value, and we set those aside when we can’t define the associated harm. This filtering process distills the raw data into what is most relevant and moves us toward the most valuable insights for the project.

Develop Solution Criteria

The statement of harm or opportunity can then be translated into solution criteria for the project. The criteria point the team toward new ideas and serve as the first step in crossing the boundary from defining the context to defining the form. With a rich set of well-formed criteria, the team gains a much clearer understanding of the problems to be solved. These criteria are a critical component of future decision-making, as they can be prioritized and weighted to guide the evaluation of ideas.

With clearly articulated criteria, initial ideas might already begin to present themselves. One additional step can then help further expand the possible solution space.

Strategies

There will likely be many possible ways to address a well-formed solution criteria. For each criterion, consider different prompts to expand the solution space as much as possible. The goal is to stimulate idea generation by framing the problem in various ways. This way, you can explore as much of the potential solution space as possible before narrowing your focus to specific ideas. In general, you can approach any problem in one of three ways: confront the problem directly, avoid the problem entirely, or minimize the problem.

That’s the end of the lesson. Based on the footage in the 20-minute video, students easily develop more than 10 solution criteria. This collection of criteria or problem statements defines the project's context. In three hours, they create a solid sketch of that context.

“The "Tupperware lesson" was an eye-opener. The videos show where the problems were actually coming from, and the framework is one of the most practical tools I’ve learned.

It’s been incredibly helpful for organizing insights and finding clarity in messy design processes. It’s fast, effective, and powerful—it simplifies everything and helps me focus on what matters most.”

–Foundations of Interaction Design Student

Now, I want them to build on top of this lesson.

A stronger foundation

It's difficult to break free from a solution-oriented mindset. The solution is what we ultimately aim to achieve, so it feels right to pursue it directly. However, the ambiguity of not knowing where you’re headed can be stressful. Having an end goal and tracking progress toward it is reassuring, but rushing to solutions is risky. Without a detailed understanding of the problem, you’ll likely miss the mark and develop a solution that doesn’t fit.

Shifting towards a problem orientation can also lead to more meaningful responses to larger issues. Big problems can feel overwhelming, even impossible to solve. But big problems are made up of smaller, interconnected issues. By creating a detailed map of the problem landscape and addressing each smaller issue with coordinated, meaningful responses, we can create a real opportunity to tackle the larger problem.

Designers have an inherent, unbridled optimism—the audacity to believe the world can be some other, better form. If we all adopt this mindset and learn to answer one essential question, I believe the solutions to our most pressing challenges will begin to reveal themselves:

“What problem are you trying to solve?”

This was such an enjoyable read and super timely for me. I don’t think enough of us really consider what we’re trying to answer – I know it’s the weakest pint in my content process. Great example with the Tupperware, too.