The Double Diamond is a designer’s best friend—a tidy, iconic diagram that promises clarity in what is often uncertain and ambiguous work. After 25 years of practice and a few of teaching, I’ve found some weak spots. I think it’s time to replace it.

I had to do some research to figure out where the Double Diamond came from. It’s been so ubiquitous during my career, I was surprised to find astronomers hadn’t traced its origins to the Big Bang. It turns out, the popularised version came from the UK Design Council in 20031.

The Design Council is the UK’s national design advocacy group. As part of that advocacy, the Council created the Double Diamond to describe the design process.

The diamonds divide the design process into four stages—Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver—structured around two phases of divergent and convergent thinking. The first diamond focuses on understanding and framing the problem; the second, on exploring and refining solutions. The stages provide an overarching framework for organizing a growing library of design methods developed and collected by the council.

There are almost as many versions of the Double Diamond as there are design firms and independent designers — each putting their own spin on the core concept. This version, from Dan Nessler, is an excellent contribution to the canon2.

In many versions, the first diamond is called “Doing the right things.” it asks us, of all the things we could do—what should we do? Many conceptions of the design process presume the answer to this question appears out of nowhere. The first diamond posits that answering this question is work in and of itself and that designers have a role to play in it.

The second diamond is often called “Doing things right” and is focused on giving form to an idea or system. It’s a more concrete, tangible contribution, whereas the first diamond describes a more abstract one. Many people — including many designers — see the designer’s work as confined to the second diamond.

Some frameworks are useful — but they’re all wrong (apologies to George Box3). The Double Diamond has definitely been useful to me. I appreciate how clearly it articulates the strategic role design can play.

Early in my design career, I felt that I could contribute not just by creating things, but by asking the right questions—by helping to define what should be made in the first place. The Double Diamond gave me language and structure for that instinct: design isn’t only about execution, but about developing goals and deeply understanding the problems we are trying to solve.

At times, however, I’ve found the Double Diamond lacking some luster—offering vague, unsatisfying answers, or even misleading guidance. It’s an effective framework for organizing methods aimed at generating useful information, but I came to realize that what I really needed was a model for how to use that information to support decision making. To me, this is what “design thinking” is—not just generating information, but applying it to make informed decisions.

The model lies: design is never done

The Double Diamond suggests that design is a tidy, linear journey with a definitive endpoint. If we simply march through two rounds of diverging and converging, we’re led to believe we’ll arrive exactly where we want to be. That sharp point at the end of the second diamond implies certainty and completion—but that’s not how it works.

In reality, design is an ongoing, nonlinear process that demands constant decision-making with imperfect information. There is no point when the team cleanly switches from diverging to converging — both are happening all the time. Our brains don’t obey phase gate boundaries — ideas can appear at inconvenient times.

For instance, during a user interview aimed at validating a prototype concept (a converging activity), a designer might hear an unexpected comment that sparks a brand-new idea, or a new question arises that requires a new research task (diverging moments). In the same conversation, they’re narrowing focus and expanding possibilities — often within minutes.

The model offers little help for the hardest part

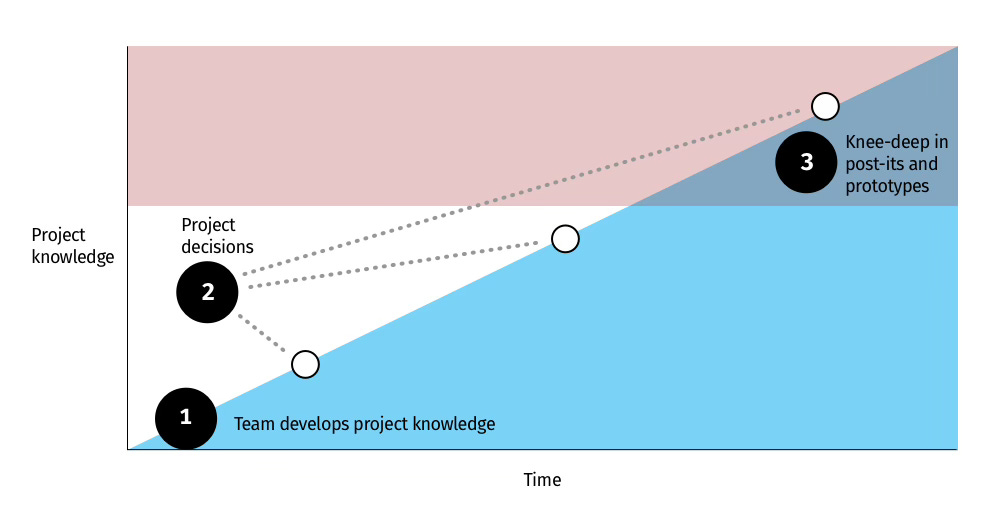

I’ve seen the same pattern play out again and again. A design team sets out to learn about a new domain, with activities that generate lots of information—stakeholder interviews, ethnographic research, brainstorming sessions, and prototyping. In the early phases, everyone can still recall what’s been learned. It’s relatively easy to arrive at a shared point of view, make decisions, and move forward.

Then it gets harder. The team is wading through knee-deep post-its or sprawling digital whiteboards. Not everyone seems to be on the same page about what’s been learned. Over time, each team member develops a different mental model of the project. Without a shared point of view, decision-making becomes strained. Everyone arrives at their own perfectly rational—but often conflicting—perspective on what should happen next.

The Double Diamond doesn’t help a team re-align at this stage—it instructs us to synthesize a point of view made of “emerging themes” and “insights” and other vagueries, but little guidance on how to do that and use the information generated during the project to move forward.

Something new

After seeing this pattern repeat throughout my career, I was motivated to find a better way. I wanted to apply design methods to increasingly complex challenges—projects involving multiple stakeholders, numerous customer touchpoints, and a wide array of interconnected issues.

I was looking for more than hand-waving, shrugging, and “you know it when you see it” explanations for how designers can make good decisions in ambiguous and uncertain environments.

What I needed wasn’t just a way to generate more information. I needed a way to use that information—to structure it, align around it, and support better decision-making.

Like so many designers, I made my own model.

The Design Decisions framework is my synthesis of two core influences: the structured, analytical approach to design I learned at the Institute of Design in Chicago, and the more exploratory, inventive methods I practiced at IDEO.

In a future post, I’ll share the Design Decisions model — a practical, flexible approach to structuring information to support decision-making in complex systems design.

Design Council. (n.d.). The history of the Double Diamond. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond/history-of-the-double-diamond/

Dan Nessler, “How to Solve Problems Applying a UXDesign, DesignThinking, HCD, or Any Design Process from Scratch (v2),” UX Collective, August 30, 2018, https://uxdesign.cc/how-to-solve-problems-applying-a-uxdesign-designthinking-hcd-or-any-design-process-from-scratch-v2-aa16e2dd550b.

All models are wrong, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_models_are_wrong

Whoops my Dad pointed out that I forgot the caption for my "project teams drowning in information" drawing... In case it didn't make sense before maybe it does now! Thanks Dad... I should have you edit it BEFORE I publish next time.

Are you familiar with Hugh Dubberly's large collection of design processes (gathered 2008)? Also, that reminds me of Bill Buxton's (Microsoft) work that I first encountered around the same time.